J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851)

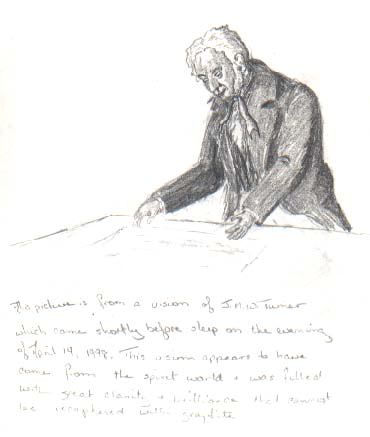

This picture is from a vision of J.M.W. Turner which came shortly before sleep on the evening of April 14, 1998. This vision was filled with great clarity and brilliance that cannot be captured with graphite, a clarity and brilliance that left me with the sense that it was more than just an ordinary dream.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (b. 4-23-1775, d. 12-19-1851, both in London) is probably one of England's greatest landscape artists. Certainly he is one of the most underappreciated. It is difficult, if not well-nigh impossible, to find popular prints and posters of his work. Print stores will have racks and racks of inexpensive framed prints of well-known works by Monet and Picasso. But try to get a Turner print and you had best be prepared to order from the publisher, wait an inordinate length of time, frame it yourself, and still pay through the nose.

Turner was not an easy man to understand, and he did not try to be. Introverted by nature, he became increasingly solitary as the years went by. He never spoke of his mother, who had died insane in a time when the medical profession's understanding of mental illness was scarcely above the witch-doctor stage. He never wed, and he observed such a strict secrecy about his relationships with his two successive mistresses (by which he is known to have fathered at least two children, and possibly more) that it is difficult if not impossible to know what they may have meant to him. His only publicly-acknowledged close relationship was with his father, who became his studio assistant and general factotum for many years and whose death was said to be emotionally devastating to the son.

Turner's reputation has not been helped by biographers determined to see all his actions in the worst possible light. His preference for solitude must have been the product of a misanthropic personality. His determined reticence about his mother had to mean that he hated and despised her. Even his close relationship with his father had to be twisted into something nasty -- he was exploiting the old man instead of giving his father a comfortable retirement.

It seems to me that Turner deserves a more sympathetic treatment by the historians of art. In fact, some people are naturally introverted, preferring their own company and not needing a constant social whirl to feel fulfilled. This is typical of artists, who generally need quiet and solitude in order to create -- it's hard to paint when you're constantly interrupted by people wanting to fill the time with idle conversation for its own sake.

The few people who got to know Turner well all report that he was a man capable of intense emotion -- a far cry from the cold, unfeeling man that certain biographers would make him out to be. In fact, it appears that he walled himself off from strangers at least partly because of his capacity for such depths of feeling. He may well have feared that, were he to allow anyone and everyone to provoke his emotions so, they would quickly suck him dry and leave nothing but a hollow shell.

Seen in this light, his attitude toward his mother takes on a different, less sinister aspect. Far from being evidence of hatred or contempt, his extreme reticence about her may well have been the result of a love so intense that he could not bear the pain of it. His anger at others' mentions of her may have been a reaction of self-defense against the emotional anguish that the reminders provoked, an anguish that left him vulnerable in a way that threatened his core being.

And what about the accusations that he exploited his father in order to avoid the expense of hiring a studio assistant? We are only now beginning to understand how able-bodied people respond to a retirement of complete idleness. Turner's father was the sort of man who needed activity and a sense of accomplishment to give him purpose in life. After his barbering business failed due to a change in fashions among the rich, helping his son gave him something meaningful to do. Had Turner done what his detractors wanted, he might as well have put his father in the coffin then and there.

Whatever complaints may be leveled against his personal life, we should not allow it to bleed over into our judgement of his work. Even in reproduction, Turner's luminous handling of his subjects have the capacity to move the receptive mind to awe, even tears. Yet he seems to be forgotten.

In his time he was ridiculed and mocked. Audiences of those times wanted near-photographic realism in the treatment of material objects, not an exploration of the subtle interplay of light and atmosphere. They wanted a magic window onto idealized bucolic scenes, not the artist's visceral reaction to the elemental violence of actual nature.

Times have changed. The Impressionists have taught us to appreciate the subtleties of the fleeting moment captured by the artist's brush. Now that we have photography to do the job of simply recording events and objects, we are able to more fully appreciate the role of the artist in interpreting those things and capturing the spirit of a subject, rather than merely the material facts. Yet Turner remains oddly ignored, as though history had left him behind. Only a few conisseurs recognize his role in anticipating the great art movements of the twentieth century.

Check The Turner Room for books on this elusive artist.

Check out these links to other people's pages on Turner

Take a look at some of the ways Turner has inspired my own art

Last updated January 11, 2014.